The online ad industry is in the midst of a healthy debate thanks to Apple’s recent moves in iOS 9 and latest Safari version. Apple now supports blocking ads through third-party iOS apps (Purify, Crystal, and 1Blocker are few examples of such apps). Apple makes miniscule ad revenues, claiming its iAd platform exists only to support app developers (also realizing that its core competence is in designing sleek, addictive, and interconnected consumer products). With iOS 9, Apple began allowing customers to download and install ad-blocking apps starting the fierce debate.

Interestingly, consumers have had the opportunity to block ads in their web browsers for many years, but only a sliver of users did. But in recent years, thanks to the innovations in ad formats, growth in mobile and video ads, more and more consumers are blocking ads. IAB claims that 34% of online users have some type of ad blocking solution. With Apple’s dominance in mobile devices, and the dramatic shift in consumer’s screen time to mobile, blocking ads is becoming easier than ever. And the ad blockers seem to work well for the most part (there is evidence that some legitimate publisher sites crash after the installation of ad blockers).

Naturally, ad tech companies, IAB, Google, Yahoo are crying foul. Historically, ad blockers were free open source software. Now ad blockers are attempting to monetize through two business models: an app install fee from the consumer (which seems fair since consumers choose to install and benefit from improved surfing experience) and/or charging advertisers/publishers for pass-through “good quality” ads (along with it comes notions of what is good quality since quality should be in the eyes of the consumer and not the publisher/advertiser).

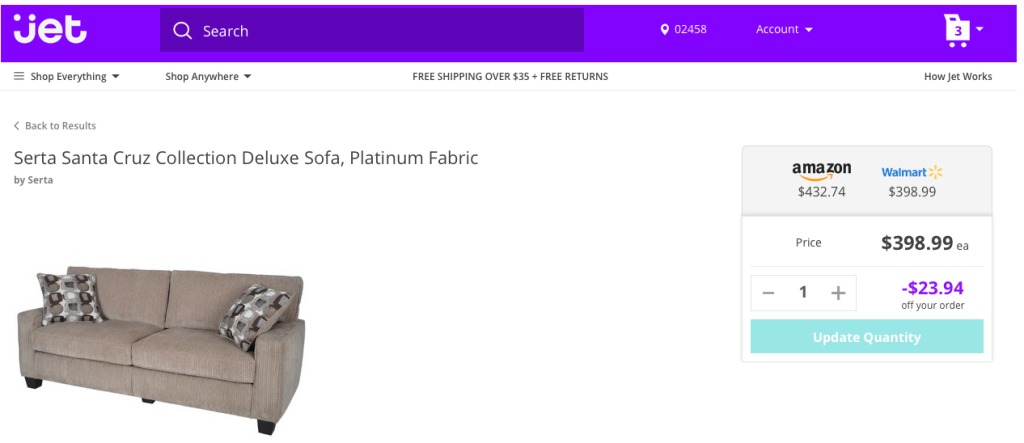

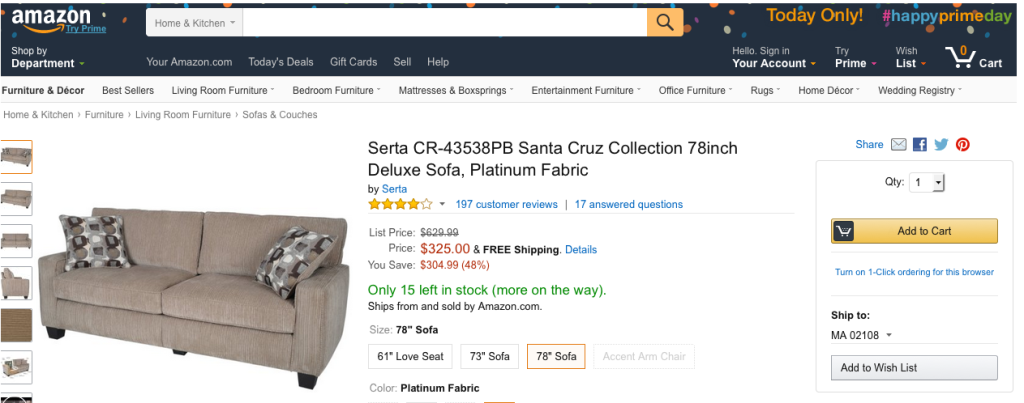

Why do ad blockers exist in the first place? Consumers are annoyed by irrelevant and intrusive ads (ads which take-over a site, automatic video plays, etc.) and concerned with security. Mobile video ads consume scarce mobile bandwidth, worsen the browsing experience (a recent New York Times article claims that a Huffington Post article loads in 1.2 seconds without ads while it takes 5.2 seconds with ads), and decrease battery life. The charts associated with the NYT article highlight a revealing story of the relative mix of ad content and editorial in popular news sites. Publishers need to reconsider the notion that their content is given away “free” to the consumer. Content is never free, since the consumer is paying for it for bandwidth and service to the internet service provider. For example, as per the same NYT article, viewing the home page of boston.com, the consumer pays a whopping $0.32 in terms of bandwidth costs.

Interestingly, given there is a real consumer need and associated value potential, ad blockers are also innovating with different mechanisms (and business models) for blocking ad content:

- Browser-level: This is the mechanism adopted by the oldest ad blockers which are installed as browser plugins/extensions. If you use multiple browsers, you will need to install the ad blocker for each browser.

- Device-level: The app based blockers spurred by iOS 9 correspond to software you install on the device, and the ad content is blocked by the blocker. Interestingly, the ad blocker can’t block in-app ads (Apple is crafty and unwilling to antagonize its developer base).

- Network-level: As per a recent WSJ article, a small Israeli startup (Shine Technologies), blocks ads at the network level, and Caribbean-based wireless provider Digicel announced that it will start blocking ads reaching its subscribers by default. Further, it will start charging for ads passed through. Digicel claims that about 10% of data consumed by its consumers is “ad content” (but the aforementioned NYT article suggests it is closer to 50%). T-mobile is considering a similar network-level ad filtering in Europe. From a consumer perspective, this is the easiest ad blocking solution (since it needs no installation of software). Network players have large capital outlays to support unprecedented growth in data traffic, more wireless operators (and wired operators as well) will be pushing for this solution. Network-level solutions will support some level of consumer control (through white-lists of publishers/advertisers). We expect to see significant migration of value in the ad ecosystem to network operators.

What should advertisers do? IAB claims that ad prices will have to pay premium prices in the future with a shrinking inventory. We claim that advertisers should embrace ad blocking of any form. Why? If a consumer does not want to be reached through ads, why should the advertiser pay to reach that consumer? Ad tech firms biggest challenge, at least in a direct response advertising space, is identifying the consumer likely to “respond” to the ad. If consumers opt-out of advertising, by design, they are also very unlikely to respond to ads. Even ad tech firms should appreciate the notion that the ads won’t be served to non-responsive audience. Ad blockers (partially) solve Wanamaker’s century-old advertising problem.

************************

Where are we heading? Apple (Samsung and other mobile device manufacturers will follow) will win. Advertisers will (unintentionally) win. Google, ad networks, and publishers will lose. Software-based ad blockers will thrive for a short while and ad value and power will shift to wired and wireless network operators embracing network-based ad blockers.

Publishers will be the ultimate losers, forcing them to develop a medley of mechanisms to monetize the content – beyond ads and subscriptions – personalized to each individual visit/visitor. We expect new ad tech entrants to help publishers navigate the new world. Publishers will need tools to identify and inform users with ad blockers and educate them; also to deny content and permit adding the site to “white list” to consume the content, i.e., permit an acceptable value exchange between the publisher and a consumer. Additionally, publishers will attempt to grow its native advertising (more on native advertising in a future post) to circumvent the ad blockers.

And as a byproduct of different ad blocking mechanisms, ad fraud will decrease, since more fraudulent “sites” and ads will become part of the dark web. Consumers and advertisers rejoice!!!